What Every Statutory Branch Auditor of a Bank Should Do. This article is an attempt to suggest some critical basics – minimum must do’s – addressing these requirements, to be taken into account by the auditors in their statutory bank branch audits. Now check more details for “What Every Statutory Branch Auditor of a Bank Should Do” from below….

What Every Statutory Branch Auditor of a Bank Should Do

1. Collecting Branch Profile and References

Collecting branch profile beforehand proceeding to the branch helps in several ways. It helps in acquainting with the type/nature, size, business and operations of the branch in advance and allows the auditor enough time to perform audit procedures at the branch. Besides documenting the audit simultaneously, it enables auditor to allocate appropriate time and resources for audit, and helps avoid chances of omissions/lapses. Though no structured format could be comprehensive and standard for all branches, yet a format to collect some firsthand critical information to plan further audit procedures is suggested in Annexure A

In addition, collecting relevant references is another such vital information that the auditor should collect as soon as the appointment process is over and before proceeding to the branch. Closing guidelines, policies, procedures and other operational guidelines of the bank are such key references to be obtained well in advance to prepare for auditing. Specifically, for most LFAR comments, auditors are required to evaluate and comment on adherence of bank’s various policies, procedures, guidelines and instructions of higher authorities; hence collection of such reference in advance is indispensible.

2. Comparing Quarterly Cost of Deposits (CoD) and Yield on Advances (YoA)

Standard on Auditing SA 520-Analytical Procedures mandates analytical reviews to be carried out by the auditors. In statutory branch auditing, a little preliminary analysis at planning stage is crucial. Especially, the comparison of quarterly cost of deposits (CoD) and yield on advances (YoA) with quarterly figures within the year and with that of the corresponding quarters of previous year could be a good preliminary reasonableness test for the audit of financial statements, revealing inconsistencies, if any, during the year.

The Auditor should obtain and document management’s explanations/reasons for abnormal variances, if any, and should consider investigation, if not explained satisfactorily, for potential misstatements/window dressing, accordingly

3. Comparing Near Quarter End Deposits and Advances

Comparing near quarter end deposits and advances with those immediately before and after quarter ends is a must-do on a bank branch auditor’s checklist that helps suggest indications of potential windowdressing, if any. For example, sudden/abnormal spurt or downfall caused due to debit entries in unutilised or under-utilised credit limits by transferring into current/savings accounts meeting CASA targets and reversing those immediately after year end.

In addition, to substantiate such debits and credits and reversal thereof after year end, the auditor should consider scrutinising the transfer journals also, particularly for 30-31 March and 1-2 April. The Auditor should specifically ask for substance/ customers’ debit authorities in such instances. Also, this transfer journal would help indicate transfer credit entries in poorly transacted/overdue credit limits, if any.

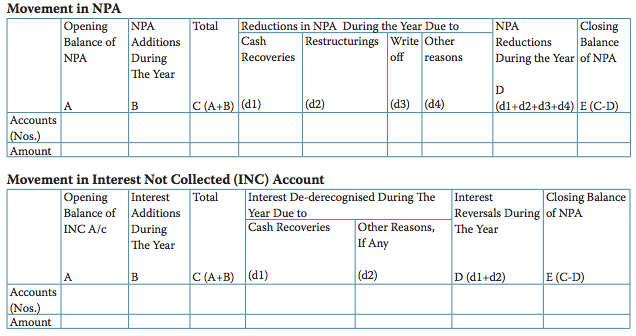

4. Scrutinising the NPA and Interest Not Collected (INC) Movement

Simple preliminary scrutiny of movement in NPA and INC account helps indicate apparent inconsistencies, if any, in these accounts. Very common reasons for such inconsistencies include incorrect interpretation/application of IRAC norms or non-marking of NPA status in the system. Reconciliation of movement in NPA and interest not collected (INC) could be obtained in the following suggested format:

Above collected information would help the auditor scrutinise and evaluate the appropriateness of income recognition, such as:

- Account-wise reconciliation of NPA additions with additions in INC account would indicate fresh NPA accounts in which interest has not been derecognised during the year. Suggestively, this should also be compared with interest failure reports for non- application of interest in such fresh additions and the listing of dummy (NPA) ledger generated from CBS;

- Account-wise reconciliation of NPA reductions with interest de-derecognised during the year (INC account) would indicate instances of not recognising the interest in NPAs upgraded during the year. Reductions in NPAs should also be cross-checked with recoveries in NPA accounts.

Comparing cash recoveries in NPAs with reductions in NPAs would help evaluate whether cash recoveries during the year have been appropriated towards interest and principal as per the bank’s policy complying with the technical/financial norms of the bank.

5. Scrutinising Asset – Classification Sheets

Different banks have different asset-classification packages customised and integrated with their main CBS packages. Currently in most banks, identification of NPAs is automated while marking of NPA status in the system is controlled manually. Omissions in marking of NPA status in the system or the manual alterations lead to incorrect asset-classification and recognition of income. Hence, before going through the asset-classification sheets, auditor should first ascertain about bank’s NPA identification and marking guidelines/methods in place-manual, partial automation and full automation. Few banks have graded system of asset-classification, for example, credit limits up to rupees one crore identified and classified automatically while beyond this limit, identified/classified manually.

Having ascertained this, the auditor should obtain customer-ID wise balancing-report for advances and should ensure matching of totals of advances and NPAs in this balancing report with that appearing in asset-classification sheets and in the balance sheet. In fact, merging of all IDs of a customer into an unique customer identification code (UCIC)- as mandated by the RBI Circular DBOD.AML. BC.No.109/14.01.001/ 2001-12 dated June 8, 2012-is critical not only for IRAC norms compliance but for TDS provisions also.

Now, go through the asset-classification sheets and just have a cursory glance-as firsthand reasonableness check-which would help indicate apparent inconsistencies/errors resulting in potential material misstatements, in critical fields, say, limit, value of securities, date of NPA, and asset-class and asset subclass. For example,

- In limit field, data erroneously fed as 9999999999 causing adverse effect on financial statements/ capital adequacy of the bank;

- Asset-class apparently inconsistent with NPA dates. For example, NPA date as 31.03.2002 and asset class as substandard; and

- Inconsistency in loan period and asset classification status. For example, loan sanctioned in the year 2000 for five years still persisting as standard.

System generated mismatching reports, if available, would also help indicate such inconsistencies, if any. Similarly, scrutiny of worksheets of provisions would help indicate discrepancies, if any, caused due to value of securities fed incorrectly in the system or due to incorrect feeding of asset-class/asset-subclass.

6. Scrutinising Modifications in Limit History

Banks’ current CBS application packages generally create logs and provide reports for modifications made in limit history, for example, ACLH menu in finacle, and are of much help to the auditor. The Auditor having obtained such modification reports, particularly for year-end quarter, should check whether all the modifications made are duly authorised by competent authorities and are in compliance with the bank’s policy/guidelines. Instances of non-compliance may include modifying the limits as ‘reviewed’ without/ incomplete financial data or review of limits by branch beyond delegated authorities. For example, a limit overdue for review pending submission of financials, modified temporarily by the branch in the system as ‘reviewed’.

Auditor should check whether necessary financials complying with bank’s credit policy/ guidelines, have been obtained and instructions of higher authorities have been adhered scrupulously in such limits.

7. Scrutinising Account Turnover Reports (ATOR)

System generated account turnover reports (ATOR), providing vital information, help in a good way to the auditor, particularly in the audit of cash credit and over draft limits. For example,

- Cash credit accounts with poor credit turnover not servicing even the interest in a given quarter could be easily determined to evaluate the appropriateness of asset- class;

- Maximum debit amounts in the account would help indicate excess/ad hoc allowed, if any, suggesting potential instance(s) of sanctions beyond/transgressing delegated authority; and

- In KCC accounts, credit amounts in 12 or 24 months after disbursements could be known at a glance to evaluate the appropriateness of asset– classification and income recognition.

Especially, the poorly transacted CC limits (against stocks)-suggestive of potential depletion in the value of primary securities/adverse features– should be checked for submission of financials and their review/renewal status. Auditor should check and determine the availability/adequacy of securities in such poorly transacted limits-long overdue for review and not submitting the financials. Recent unit-inspection reports, if available in such accounts, could help determine the availability of securities and appropriateness of their asset-classification. Similarly, in OD limits, debit-credit turnover would help ascertain servicing of interests during the quarter and their asset classification and income recognition.

8. Using Early Alert System (EAS)/Special Mention Accounts (SMA)/Status Reports

Banks’ credit monitoring systems generally provide various monitoring reports for follow-up purposes, such as EAS/out of order/potential NPA/SMA reports. The Auditor can make best use of this information. Particularly, the potential NPA/special mention accounts, overdue due to repayment defaults or due to reviews/renewals, appearing in December quarter reports should be checked whether these have been regularised/reviewed appropriately as per bank’s norms. These should be checked for whether such accounts have been reviewed/renewed obtaining relevant financials/ documents adhering bank’s guidelines and have been classified appropriately.

In addition, periodical status reports on large borrowal accounts submitted to the controllers and internal audit reports, throwing enough light on overdue/adverse features, could also be a good firsthand input for auditor’s evaluation of IRAC norms/LFAR comments.

9. Scrutinising Impersonal (Sensitive) Ledger Accounts

Impersonal accounts, also called as sensitive accounts, are the accounts not belonging to customers and maintained by the banks for their own operational purposes. Few of such very common accounts/ account-groups are suspense, sundries, intermediary, clearing, branch adjustments, POB, proxy, parking, bills payable and others/miscellaneous. These are considered as highly exposed to the risk of potential override of controls/transgression of delegated authorities by management and need special care by the auditor.

Suggestively, besides obtaining the age-wise breakup of entries, auditor should obtain full ledger for the year for such accounts-regardless of zero balances at year end, and should inquire into the large/unusual entries for their substance. The Auditor’s reviews should specifically include the transfer entries, for example, cheques in clearing/ intermediary account and corresponding credits in the NPA accounts to regularise at the year end and subsequent reversal thereof. Cheques/bills purchased without sanctioned limits and adjusted through these impersonal accounts at the year-end is another such example to be considered by the auditor

Conclusion

No audit plan or checklist can be exhaustive or panacea. This article, talking for some preliminary audit procedures, underlines the importance of auditing basics and emphasises on the need of a systematic approach for auditing. These basics, if applied appropriately, would help the auditor minimising the chances of material omissions/ lapses and the risk of expressing an inappropriate audit opinion. These would also help document the auditors’ work, meeting their legal and professional obligations simultaneously. Overall, this could serve as beginners’ guide. However, to get any audit plan implemented, the management’s vehement cooperation is the key. Management should demonstrate its cooperation by providing required information promptly beforehand and during the audit to get it accomplished timely and in a purposeful manner.

Recommended Articles